A broad and beautiful Vincente Minnelli musical (1948) with a rich score by Cole Porter. In a Technicolor Caribbean, traveling player Gene Kelly is in love with demure maiden Judy Garland, but she has lustier fantasies, pining after the magnificent pirate Black Mococo. Lively, colorful, and lyrical—Minnelli was married to Garland at the time, and it shows in some of the most romantic close-ups ever put on film. 102 min.

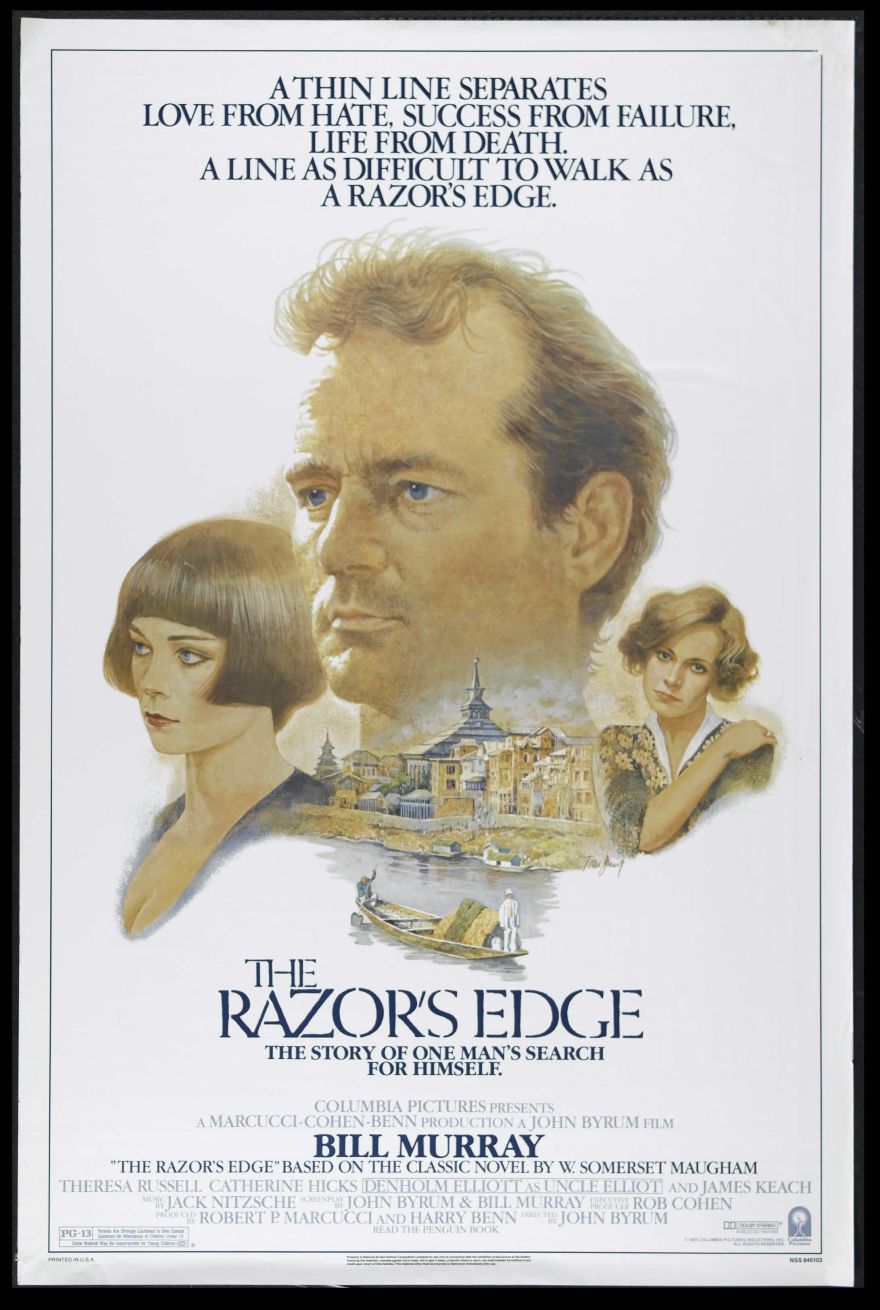

Kehr’s Weekly Recap: The Razor’s Edge (1984)

Unsettled by his experience in World War I, Lake Forest cutup Bill Murray resigns the shallow materialism of his friends and fiancee and sets out on the narrow path to spiritual enlightenment. This intensely embarrassing film clearly has great personal value for Murray (the real-life parallels become chillingly explicit when a subplot introduces a dope- and booze-addicted friend whom Murray is unable to save), but if the motivations are authentic, the result is anything but. The screenplay (cowritten by Murray and director John Byrum) shies away from specifying Murray’s spiritual achievements; instead of maturing, the character simply becomes more smug and condescending, and the movie’s ultimate subject is his fatuous self-satisfaction in the face of the other characters’ carefully delineated weaknesses. Not one moment in the film works the way it was plainly meant to. With Theresa Russell, Catherine Hicks, and Denholm Elliott. PG-13, 128 min.

Continue reading “Kehr’s Weekly Recap: The Razor’s Edge (1984)”

Kehr’s Weekly Recap: Moonlighting (1982)

Conceived and shot in the space of a few weeks due to the Solidarity crisis of December 1981, Jerzy Skolimowski‘s black comedy is much more than a political tract: it’s a profound, gripping comedy of terror and isolation, oppression and entrapment. Jeremy Irons, in a performance worthy of Chaplin, is the head of a Polish construction crew doing illegal work on a flat in London; when the military coup occurs back home, Irons—the only member of the group who speaks English—must keep it a secret from his men. Though the film is founded on a metaphor, it is never forced or abstract: Skolimowski’s direction is a concrete creative response to these actors in this setting at this time, making full expressive use of the details, gestures, and situations at hand. It is, in short, a film—unimaginable as theater or literature—and very possibly a great one.

Kehr’s Weekly Recap: The Red Badge of Courage (1951)

The making and unmaking of this 1951 film were described in painful detail in Lillian Ross‘s book Picture, which was for years the definitive document on Hollywood philistinism. Certainly writer-director John Huston‘s original version would be preferable to the mangled remains (it was cut to 70 minutes during a power struggle between Louis B. Mayer and Dore Schary), though the sequences that survive suggest that Huston’s vision was not particularly compelling to begin with. It’s the earliest example of Huston’s propensity for sacrificing the humanity of his characters to artsy camera angles and distended compositions—what he gains in graphic power he loses in emotional force. With Audie Murphy, Bill Mauldin, Royal Dano, and Andy Devine.

Continue reading “Kehr’s Weekly Recap: The Red Badge of Courage (1951)”

Kehr’s Weekly Recap: Mannequin (1937)

A minor Frank Borzage melodrama, but not without interest for students of his style. Joan Crawford is a poor girl from the lower east side, unhappily married to a petty crook, who finds relief with Spencer Tracy, a self-made millionaire. Borzage’s gift for compact, succinct, visual metaphor is evident in his use of a flickering lightbulb in the stairway of Crawford’s tenement apartment; it becomes, in the space of a few frames, a heartbreaking symbol of dying hope. With Alan Curtis and Ralph Morgan (1937).

Kehr’s Weekly Recap: Love Me Tonight (1932)

Rouben Mamoulian‘s thrilling and innovative 1932 musical with Jeanette MacDonald, Maurice Chevalier, Myrna Loy, and Charles Ruggles, with a fine Rodgers and Hart score that includes “Isn’t It Romantic?” and “Lover.” Similar in many respects to the Lubitsch musicals with MacDonald and Chevalier during the same period, although Mamoulian’s lively experiments with rhythm, framing, and superimposition are very much his own. 104 min.

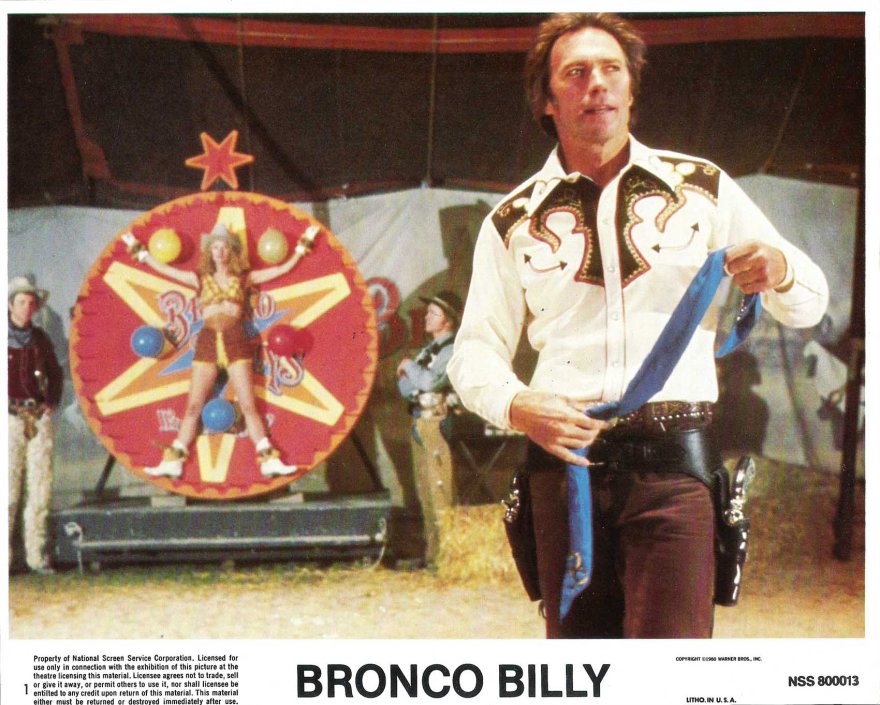

Kehr’s Weekly Recap: Bronco Billy (1980)

A gentle fable on familiar themes, lightly salted with irony by Clint Eastwood. Eastwood plays the title character, the head of a modern-day wild west show that scrabbles from town to town in the backwaters of the midwest, spreading the forgotten values of fair play, comradeship, and clean living (up to a point). Sondra Locke, as a spoiled heiress, enters via a plot device lifted from It Happened One Night. Eastwood’s performance is dense and subtle, drawing on his natural shyness and gentility, though his direction — apart from two or three creatively edited sequences — is much less distinctive than it has been before. A minor film with a good heart — if anything, it’s too lovable (1980).

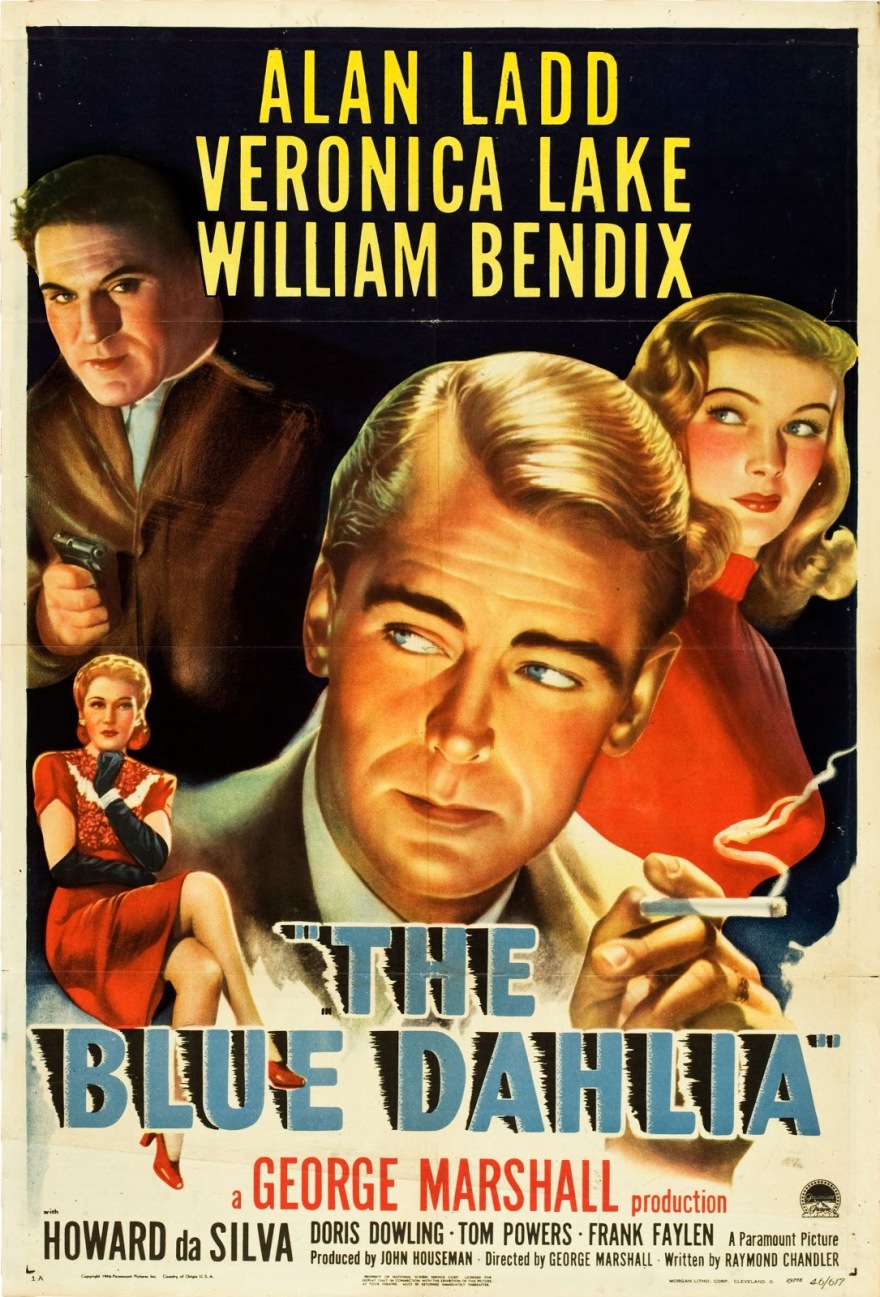

Kehr’s Weekly Recap: The Blue Dahlia (1946)

Underneath this Veronica Lake–Alan Ladd thriller (1946) lies Raymond Chandler‘s only original screenplay—a suitably hard-nosed affair about a war vet whose homecoming coincides with the murder of his unfaithful wife. Though it has the Chandler flavor and occasionally captures the feel of his sunbaked Los Angeles, the film falters under the uncertain, visually uninventive direction of George Marshall—wildly miscast here, when any vaguely sympathetic hack from Stuart Heisler to Frank Tuttle would have been just fine. With William Bendix and Howard da Silva.

Continue reading “Kehr’s Weekly Recap: The Blue Dahlia (1946)”

Kehr’s Weekly Recap: Come And Get It (1936)

A botch job by Sam Goldwyn, who exercised his power as producer by changing directors—from Howard Hawks to William Wyler—halfway through the shooting. Some sources hold that Wyler shot only the last ten minutes, working from Hawks’s script; others claim that Wyler reshot much of Hawks’s work. But the first part of the film, the best, is unmistakably Hawks, as Edward Arnold and Walter Brennan (in an early part, his first Academy Award performance) fight for the hand of Frances Farmer, against the background of the north-woods logging country. The Edna Ferber story (like her Giant) then shifts generations, and the action loses much of its scale. Farmer remains a wonder, in one of her few fully realized parts as an early and lusty version of the Hawksian woman (1936).

Continue reading “Kehr’s Weekly Recap: Come And Get It (1936)”

Kehr’s Weekly Recap: The Cobweb (1955)

Vincente Minnelli‘s 1955 melodrama is set in a posh mental hospital; he choreographs the various plots and subplots with the same style and dynamism he brought to his famous musicals. Charles Boyer is the head of the clinic, a secret alcoholic worried about competition from hotshot young shrink Richard Widmark. Widmark, in turn, is caught in a triangle with his childish wife (Gloria Grahame) and an understanding colleague (Lauren Bacall). Among the guest loonies are Oscar Levant (who sings “Mother” in a straitjacket), Lillian Gish, Susan Strasberg, Fay Wray, John Kerr, Paul Stewart, and Adele Jergens; John Houseman produced. 124 min.